Clinical Case Reports

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a young man. Case report.

Rafael Santiago Velásquez Restrepo1, María Paula Botero Franco1,

Marcela Henao-Pérez1,

Diana Carolina López-Medina1.

1 Faculty of Medicine, Cooperative University of Colombia, Medellin, Colombia.

Corresponding author’s address

Dr. Rafael Santiago Velásquez Restrepo.

Postal address: Faculty of Medicine, Cooperative University of Colombia Street 50 N 40–74, Medellín -Colombia

E-mail

INFORMATION

Received on October 31, 2021

Accepted after review

on August 10, 2022 www.revistafac.org.ar

There are no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Keywords:

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Men.

Young adult.

ABSTRACT

The case of a 27-year-old male patient is described, who was referred to a highly complex hospital

after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was suspected. After performing an angiography,

a significant involvement of any vascular territory was ruled out, which led to the diagnosis of

Takotsubo Syndrome (TTS). This disease is more prevalent in postmenopausal women. Although it

is reported to a lesser extent in men, it has been seen that in them, there is a higher rate of complications,

mainly when it occurs in young patients. In turn, the diagnosis in this population is usually

delayed due to its severe forms of presentation and the little suspicion that exists precisely because

of the limited data currently provided by epidemiology.

INTRODUCTION

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is an acute transitory ventricular dysfunction that is characterized by anomalies in the ventricular walls kinetics, not attributable to an alteration in a single vascular distribution, accompanied by elevation in cardiac biomarkers and electrocardiographic (ECG) changes in absence of atherosclerotic disease, which makes it an important differential diagnosis with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Its prevalence is greater in postmenopausal women; however, it has been observed that outcomes are usually worse in young men, such as: cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmias[1,2,3,4,5,6]. We present the case of a young male patient with diagnosis of TTS, with a 4-year follow-up.

CLINICAL CASE

Male, 27-year-old patient. He was single, living with his parents and sister, industrial electrician. He initially consulted due to symptom of intense chest pain of sudden onset in precordial region. Pain was oppressive, not radiated, of 10/10 intensity, associated to profuse diaphoresis, pallor, asthenia and weakness. ECG was performed, where ST-segment elevation was verified in inferior wall, so it was decided to perform thrombolysis with alteplase, displaying positive reperfusion criteria, so he was referred to the coronary care unit of an institution of greater complexity. On admission to the unit, he reported improvement in pain, at the time only associated to movement. No significant personal or family history was found related to cardiovascular disease, he denied consuming psychoactive or stimulating drugs, and he only reported occasional alcohol consumption.

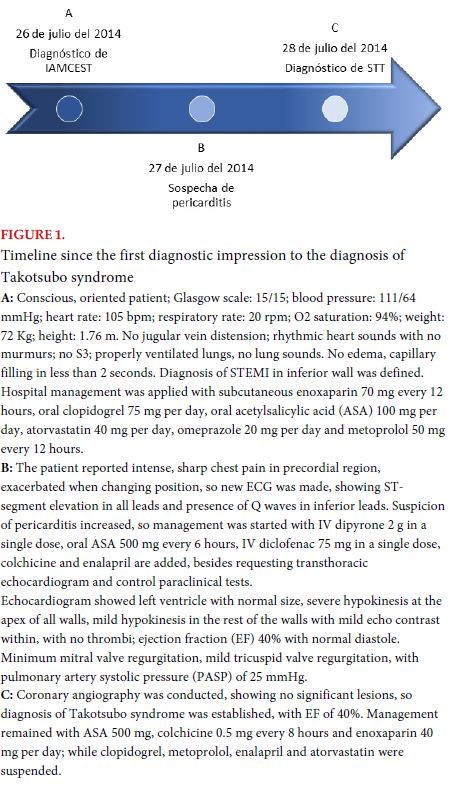

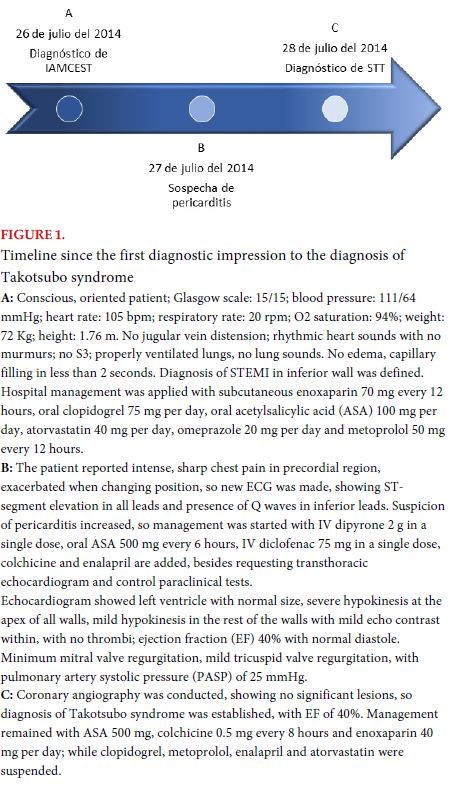

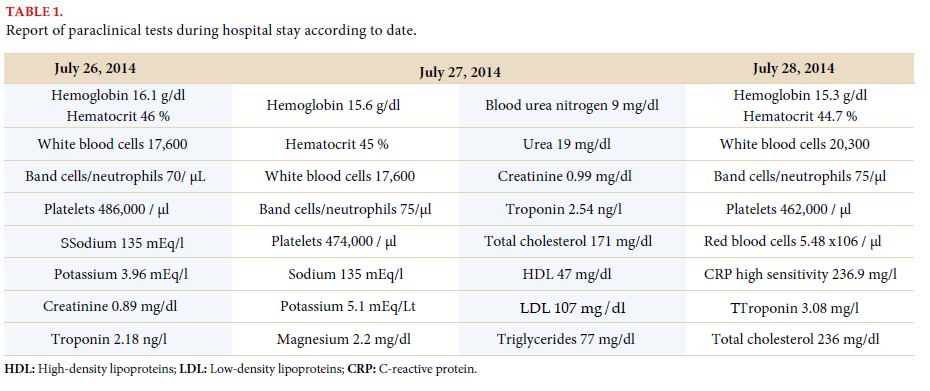

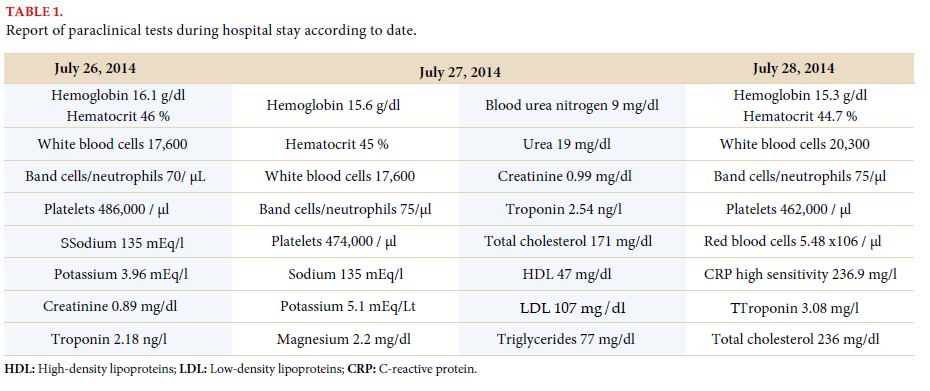

During physical examination, the patient was found to be in good general condition, with hemodynamic stability and no signs of heart failure. Diagnosis of STEMI of inferior wall was established, and pericarditis was suspected, so he was administered pharmacological treatment for both entities. Precordial pain recurred, so echocardiogram was conducted, which was pathological; coronary angiography, which did not show coronary artery lesions (Figure 1) and laboratory tests (Table 1), reaching the diagnosis of TTS.

After three days of hospital stay, he was discharged with an appointment for cardiological monitoring in 3 months, with control echocardiogram. Twelve sessions of cardiac rehabilitation were indicated.

In the echocardiography made 3 months later, the left ventricle presented normal size, morphology and global and segmentary function, EF was 60% and diastole was normal. Minimum mitral valve regurgitation, minimum tricuspid valve regurgitation, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP) of 25 mmHg. In cardiological monitoring, the patient was asymptomatic, with no medication and in good general condition, so he was given an appointment for 6 months later for follow-up, finding a good clinical course.

In the most recent echocardiography, performed 4 years after the diagnosis, the left ventricle was found to be normal in size, morphology and global and segmentary function, and EF 65%, normal diastole, minimum physiological mitral valve regurgitation and minimum tricuspid valve regurgitation, with PASP of 23 mmHg.

DISCUSSION

TTS, also known as broken heart syndrome or stress cardiomyopathy, is a transitory acute ventricular dysfunction that is characterized by anomalies in the kinetics of ventricular walls, not attributable to alteration in a single vascular distribution, accompanied by elevation in cardiac biomarkers and electrocardiographic changes in absence of atherosclerotic disease, which turns it into an important differential diagnosis with AMI and Prinzmetal angina[1,2,3,4,6].

Prinzmetal angina is a frequent pathology in men, which increases incidence proportionally to age (average 65 years), and is characterized by the presence of spontaneous coronary vasospasm, entailing a decrease in myocardial blood flow over a short segment, nearly always in the territory of the anterior descending artery, which is caused by imbalance in the autonomic nervous system control, with sympathetic predominance, triggered by stressor factors such as smoking or alcohol consumption.

This alteration may also be considered a differential diagnosis with TTS given that clinical symptoms and etiology may be the same in both entities[7,8].

In TTS, most patients are postmenopausal women, with a 9:1 female-to-male ratio[3,4,6]. It is estimated that in the United States, there are approximately 50,000-100,000 cases per year, with similar figures in Europe. Approximately 1% to 3% of all patients with suspicion of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and who undergo coronary angiography are diagnosed with TTS, with a prevalence of gender that ranges from 6% to 9.8% for women, and less than 0.5% for men[5]. In literature, it is estimated that only 10% of TTS cases occur in men; however, in the Asian population, a greater prevalence has been found, reaching 13% to 35%[2,5].

There are few record s in literature for TTS cases in young men; nevertheless, in a study made in Austria with a total of 179 patients, it was found that 11 of them were men, with ages ranging between 38-88 years[4]. Likewise, a study made in 11 countries ratified that the prevalence of the disease in men was inversely proportional to age, being 12.4% in those younger than 50 years of age, and 6.3% in those older than 75 years[3].

In up to 70% to 80% of cases, the cause of cardiomyopathy is established, and from them, emotional stress represents 40% in general[5]. It has been described that physical stress, just as stress due to acute noncardiac diseases, or surgical or diagnostic procedures may trigger TTS more frequently in men than in women (35% in comparison to 14.2%, respectively)[2,5,7,8]. Furthermore, it has been seen that men who develop TTS have more chances of living alone than women, as well as having the habit smoking, 24.4% in women and 57.1% in men[2]. Also, the relationship between psychiatric diseases and TTS development is important, because both the pathologies and their management may trigger the disease (up to 70% of patients with TTS have a neuropsychiatric disorder associated, such as epilepsy, stroke, mood disorders and anxiety)[3,9,10]. In the case reported here, no associated stressor or neuropsychiatric comorbidity was identified.

The main clinical symptoms are dyspnea and chest pain, with the latter being more frequent in women; while dyspnea, syncope or any other symptom presents similarly in both genders. Young patients are more prone to developing complications such as cardiogenic shock (11.9%), cardiac arrest (3.3%) and ventricular arrhythmias (6.8%), or for these to be the initial symptom of the disease; therefore, diagnosis could be delayed[5,7,11]. Additionally, it has been found that men have a greater need to receive cardiopulmonary support, and that being male acts as an independent predictor for adverse cardiovascular events and mortality[5,11,12]. In the Japanese population, for instance, the autopsy of patients that suffered sudden cardiac death secondary to TTS showed that 85% were men[2].

The most common electrocardiographic finding is ST-segment elevation in precordial leads in up to 40% to 90% of patients, since it generates a more apical compromise, with lesions in V5-V6 being predominant[5,8,13,14]. However, in men, ECG modifications usually appear later, such as T-wave inversion or the presence of Q wave, although no significant differences have been found[5,7].

In some studies, it has been reported that in general, cardiac biomarkers show a lower level in patients with TTS in comparison to those coursing AMI. In males, lower values of N-terminal prohormone of the brain natriuretic peptide are found on admission, as well as lower ejection fraction; but creatine kinase and troponin are higher in comparison to women[2,5].

CONCLUSION

Although it is rare to find TTS cases reported in young men in literature, when the syndrome appears patients may be more prone to developing complications, and therefore, to presenting a higher mortality. The main trigger in males is physical stress, although emotional stress cannot be dismissed. In the case presented here, it is not known if there was a triggering event, and the course was favorable, possible due to a timely diagnosis and management. Given the relevance of psychosocial factors in TTS, an initial management by psychologists or psychiatrists and a multidisciplinary treatment play a significant role in these patients.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Shufelt CL, Pacheco C, Tweet MS, et al. Sex-Specific Physiology and Cardiovascular

Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018; 1065: 433 - 454..

- Budnik M, Nowak R, Fijałkowski M, et al. Sex-dependent differences in

clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes in patients with takotsubo

syndrome. Pol Arch Intern Med 2020; 130: 25 - 30

- Cammann VL, Szawan KA, Stähli BE, et al. Age-Related Variations in

Takotsubo Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 75: 1869 - 1877.

- Weihs V, Szücs D, Fellner B, et al. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (Tako-

Tsubo syndrome) in Austria. Eur Hear J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2013; 2:

137 - 146.

- Schneider B, Sechtem U. Influence of Age and Gender in Takotsubo Syndrome.

Heart Fail Clin 2016; 12: 521 -530.

- Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes

of Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 929 - 938.

- Angelini P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: what is behind the octopus trap?

Texas Hear Inst J 2010; 37: 85 – 87.

- JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of

Patients With Vasospastic Angina (Coronary Spastic Angina) (JCS 2008) -

Digest Version -. Circ J 2010; 74: 1745 - 1762..

- Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Presentation of Tako-tsubo Cardiomyopathy

in Men and Women. Clin Cardiol 2010; 33_ 42 - 45..

- Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, et al. Natural History and Expansive

Clinical Profile of Stress (Tako-Tsubo) Cardiomyopathy. J Am

Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 333 - 341.

- Zvonarev V. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: Medical and Psychiatric Aspects.

Role of Psychotropic Medications in the Treatment of Adults with

“Broken Heart” Syndrome. Cureus 2019; 11: e5177.

- Nayeri A, Rafla-Yuan E, Krishnan S, et al. Psychiatric Illness in Takotsubo

(Stress) Cardiomyopathy: A Review. Psychosomatics 2018; 59: 220 - 226.

- Liang J, Zhang J, Xu Y, et al. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors associated

with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A comprehensive review. Clin

Cardiol 2021; 44: 1033 – 1040.

- Battioni L, Costabel JP, Mondragón IL, et al. Diferencias electrocardiográficas

entre Takotsubo e infarto agudo de miocardio. Rev Fed Arg Cardiol

2015; 44: 51 – 54.