1 Sanatorio Allende. 2 Instituto de Ciencias de la Administración de la Universidad Católica de Córdoba (UCC), Argentina.

Corresponding author’s address

Lic. Mario A. Trógolo

Postal address: : Manzana 249, Lote 11, 5105 Comarca de Allende Villa Allende, Córdoba, Argentina

E-mail

Received June 16, 2022 Accepted after review on July 27, 2022 www.revistafac.org.ar

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Keywords:

COVID-19 .

Frontline healthcare workers .

Satisfaction with job resources.

Burnout

Work engagement

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic represents a major public health challenge, particularly among frontline healthcare workers. This study examines the impact of satisfaction with job resources (leader-, task-, team- and organizational-level) on burnout and work engagement.

Material and methods:one-hundred and twenty-five healthcare workers (physicians, nurses) from a private health institution filled an anonymous online survey. Seventy-six participants were females.

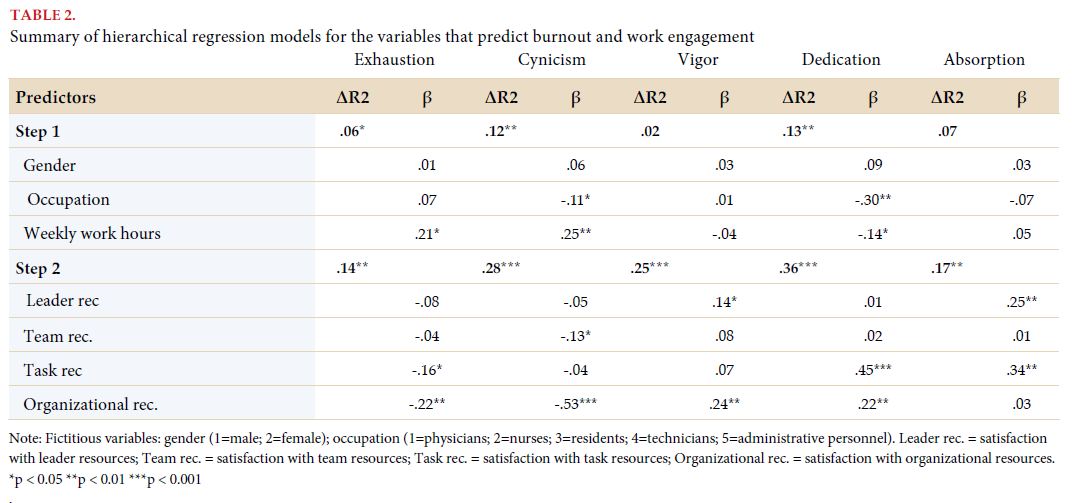

Results: Bivariate correlation and multiple regression analyses showed that satisfaction with job resources positively influences work engagement, and negatively influences burnout. In particular, regression analyses showed that burnout symptoms were mainly predicted by satisfaction with organizational resources (βexhaustion = -.22; βcynicism = -.53) and work engagement was best predicted by satisfaction with task resources (βdedication = .45; βabsorption = .34).

Conclusions: Current findings point the value of satisfaction with job resources to protect the mental health of frontline healthcare workers during health crises and extreme work overload. Suggestions aimed at reducing burnout, promoting work engagement and protecting the wellbeing and mental health of healthcare workers during future public health crises are proposed..

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, originated by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, constitutes an unprecedented event in the history of worldwide public health, with massive consequences at social, financial, cultural, and of course, sanitary levels[1]. In spite of the development of specific vaccines and antivirals, the end of social distancing and a return to “normal” life, the pandemic seems not to have concluded yet: new contagion waves (though not as intense as the first ones) happen one after the other, with the appearance of new virus mutations, exerting continuous pressure on the health care system[2]. In Argentina, since the official announcement of the pandemic, 9,313,453 positive cases were recorded, as well as a total of 128,994 deceases due to COVID-19, a fact that places it as the second country with highest mortality rate by COVID-19 in America[3,4].

Health care professionals constitute one of the groups more susceptible to experiencing mental and emotional issues during the pandemic, particularly those in the first line of care for patients infected by COVID-19[5]. The increase in pressure and work overload, shortages of supplies and personal protective equipment, the fear of getting the disease or transmitting it to family members, the death of colleagues and patients by COVID-19, the relocation to critical areas due to the collapse and staff scarcity, with no training or specific education, along with isolation scenarios, discrimination and in some cases violence to which the sanitary staff are exposed, constitutes a complex situation, highly stressful, which negatively impacts on the mental health of health care workers[6,7]. We should highlight that these problems do not constitute an immediate and transitory consequence associated to a specific time during the pandemic, since persistent negative effects on mental health are already observed in health care workers, even in periods of relative “quietness”[8].

One of the most concerning problems affecting mental health in the health care staff is burnout[9]. The latter constitutes a syndrome resulting from a prolonged exposition to different work stressors. Currently, it is considered that burnout is made up by two central dimensions (“core”): exhaustion, representing the feeling of being exhausted due to the demands of the work, and attitudes of depersonalization or cynicism, meaning negative attitudes of distancing, coldness and indifference toward the people with whom they work and the receivers of it (depersonalization), or toward work in a wide sense, not just in relation to people (cynicism)[10].

Several studies published since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic show a high prevalence of burnout in health care professions who provide care for infected patients, with values ranging between 31% and 90%, depending among other things, on the country, the area or service, and the role played by professionals in the institution, and the period when the study was made[11,12,13]. The presence of burnout in health care professionals has been associated to more anxiety and depression, more absenteeism and a desire to abandon the profession, a higher rate of medical mistakes and a longer recovery time in patients[14,15,16,17]. Consequently, it is very interesting to identify the factors that may prevent or decrease the risk of developing burnout

Satisfaction with work resources

Recently, Spontón et al. proposed the concept of satisfaction with work resources, in terms of the feeling of wellbeing of workers in relation to different factors present in the work environment[18]. These factors facilitate developing tasks, encourage individual and collective performance, favor personal development, and generate positive work environments. Specifically, according to these authors, satisfaction with work resources could be analyzed from four dimensions: (a) Leader: it covers aspects of relationship with the chief or supervisor, such as clarity of information provided, feedback and acknowledgement; (b) task: it covers the intrinsic and immediate characteristics of the workplace, such as time availability and material resources necessary to perform tasks; (c) team: it covers the social and working environment, mainly the relationship with work partners from teams in aspects related to coordination, cooperation, productivity or efficiency, and creativity to solve problems; and (d) organization: it means working conditions and organizational practices in a wide sense. It includes aspects like salary, non-financial retributions system, benefits, development opportunities, training and learning. This classification is based on the HEalthy and Resilient Organizational (HERO) model proposed by Salanova et al., but it provides more specificity to the analysis of satisfaction with work resources of the social type, by differentiating the leader or supervisor resources from team resources (work partners)[19].

Taking this model as reference, this study intended to analyze the influence of satisfaction with work resources on burnout in health care professionals. Supplementarily, the impact of satisfaction with resources on the work engagement of workers was analyzed. Work engagement means a positive psychological state related to work, categorized by vigor, dedication and absorption[20]. Vigor entails high levels of energy, effort and persistence in work. Dedication entails a feeling of enthusiasm, inspiration, pride and significance for the work done. Finally, absorption entails a state of total immersion and concentration in work, to the extent of experiencing the feeling that “time flies” and it feels difficult to get away from what is being done. Work engagement in health care workers has been related to different positive consequences, with more work and vital satisfaction, less medical mistakes, more satisfaction of patients and less levels of burnout[21,22,23,24].

Recent studies during the context of the COVID-19 pandemic indicate medium and high levels of work engagement in health care workers[24,25,26]. For instance, Meynaar et al. found a sample of Dutch physicians working in the intensive care unit, with COVID-19 patients, with medium (50.6%) and high (38.9%) levels of work engagement[24]. These results show the existence of health care workers engaged even in contexts of crises, uncertainty and high demand, so it is interesting to identify the factors that promote and strengthen work engagement in these workers, particularly in conditions of high stress, as that originated by the current sanitary crisis. It is important to mention that, just as with burnout, a good part of the investigations that examined work engagement in health care professionals during the pandemic, made it from an essentially descriptive perspective[27,28]. Instead, knowledge on the factors that may influence on burnout and work engagement of health care workers during the pandemic is limited; although this knowledge is of great practical interest to guide interventions addressed to taking care of the mental health of the health care staff. This study analyzes the role of satisfaction with work resources on work engagement and burnout in the health care staff in Argentina, within the framework of the sanitary crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the aims were: (1) to analyze the relationship between satisfaction with different work resources (leader, team, task and organization) and the burnout and work engagement dimensions; and (2) to examine the independent contribution of the different resources in the prediction of burnout and work engagement. Although this study is limited to a specific time in the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that the results may provide useful information for the design of proactive interventions, which will allow to reduce negative psychological impact and to protect the mental health of health care professionals in future sanitary crises.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The population of interest in this study was represented by medical staff (physicians, residents), nurses and administrative staff of public and private health care institutions of the city of Córdoba, who worked in person during the COVID-19 pandemic. The final sample was constituted by 125 workers from a private health care institution from Córdoba, which was selected by convenience sampling. Seventy-six percent of participants were women. In regard to jobs, 28% were physicians, 37.3% nurses, 21.3% residents, 9.3% corresponded to technical staff, and 4% to administrative staff. From all the surveyed individuals, 6.7% worked less than 10 hours a week, 5.3% between 10 and 20 hours, 9.3% between 20 and 30 hours, 14.7% between 30 and 40 hours, and 64% more than 40 hours per week.

Instruments

To evaluate the satisfaction with the work resources, the Questionnaire on Satisfaction with Work Resources (CSRL_16) was used[18]. This is a self-report questionnaire made up by 16 items, which enables evaluating satisfaction with the resources of leaders, tasks, team and organizational resources. All items were created according to a Likert scale of five categories ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). High scores indicate a greater level of satisfaction with resources. The score presents a proper construct validity, satisfactory internal consistency levels, and test criterion validity evidence with measures of work engagement and burnout

To evaluate work engagement, the Argentine version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) was used. The Argentine adaptation has 17 items, just as the original scale, which allow evaluating three theoretical dimensions of work engagement: vigor, dedication and absorption. Every item is answered using a reply scale with 7 categories, from 0 (never) to 6 (always). High scores reflect greater levels of work engagement[29].

On the other hand, burnout was evaluated by the Argentine adaptation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS)[30]. The original scale has 16 items grouped in three dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism and lack of professional efficacy. In Argentina, studies made on a multi-occupational sample showed that two factors, matching the central dimensions or “core” of burnout (i.e., exhaustion and cynicism), provide a better representation of data than the three original dimensions, so only these dimensions were evaluated.

Finally, an ad hoc socio-demographic questionnaire was applied, through which information was collected on gender, role or job of the workers of the institution, and number of weekly work hours

Procedure and ethical aspects

Data collection was carried out online, by a questionnaire designed through the open Google Form platform. The questionnaire was distributed by e-mail and WhatsApp to all medical staff (physicians, residents), nurses, technicians and administrative personnel of the institution, with the help of the chiefs of the different areas and services. The rate of response was high (100%). The data were collected during September 2021, a period over which the Argentine government had decreed a state of emergency due to the advancement of the second wave of contagions[31]. The study was conducted strictly following the principles established in the declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent modifications, the Code of Ethics on Research of the Federación de Psicólogos de la República Argentina – FePRA (Argentine Federation of Psychologists) and its valid updates, and the Law for the Protection of Personal Data (Law 25.326) of Argentina[32,33]. In this regard, participation was voluntary, anonymous, and all the participants provided their informed consent before answering, so a page was included in the questionnaires, where there was a thorough description of the characteristics and aims of the research, confidentiality and anonymity of replies, the right to withdraw from the study at any time and for whatever reason, and how data would be managed and their use for academic goals (papers and academic presentations). Furthermore, special care was given to questions not generating discomfort, negative emotions or disagreeable reactions in participants. Also, the contact e-mail of the main investigator (first author) was provided in order to request additional information or clarification about any aspect related to the research. We should emphasize no incentive or compensation was offered to answer the questionnaires.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with the statistical package SPSS 20.0. First, the descriptive statistical data were obtained (mean and standard deviation) and internal consistency was assessed (Cronbach’s alpha) for each of the scales. Subsequently, relationships were analyzed between the variables of the study by Pearson correlation coefficient (r). Finally, different models of multiple linear regression (hierarchical model) were estimated taking as predictor variables the satisfaction with different work resources, and as criterion variables, the different dimensions of work engagement and burnout. In each model, the total contribution of predictor variables (R2) was analyzed, as well as the independent contribution of each by standardized regression coefficients (β).

RESULTS

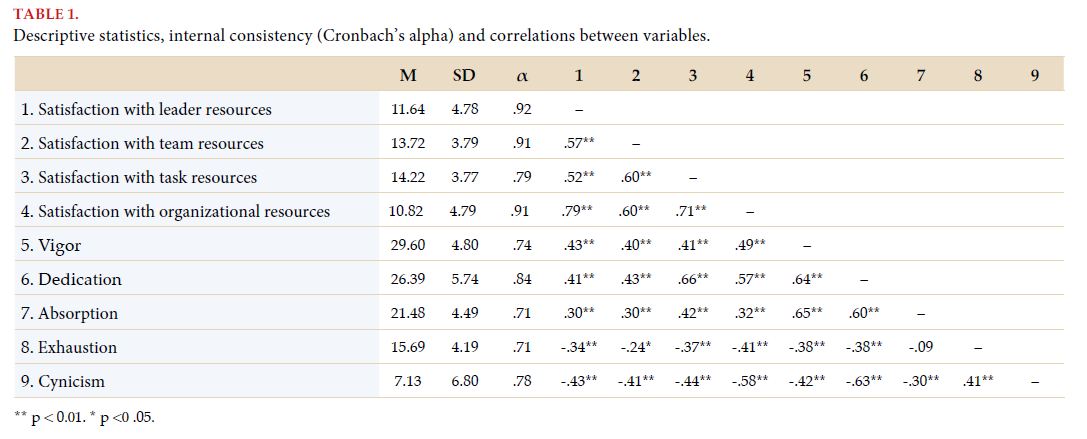

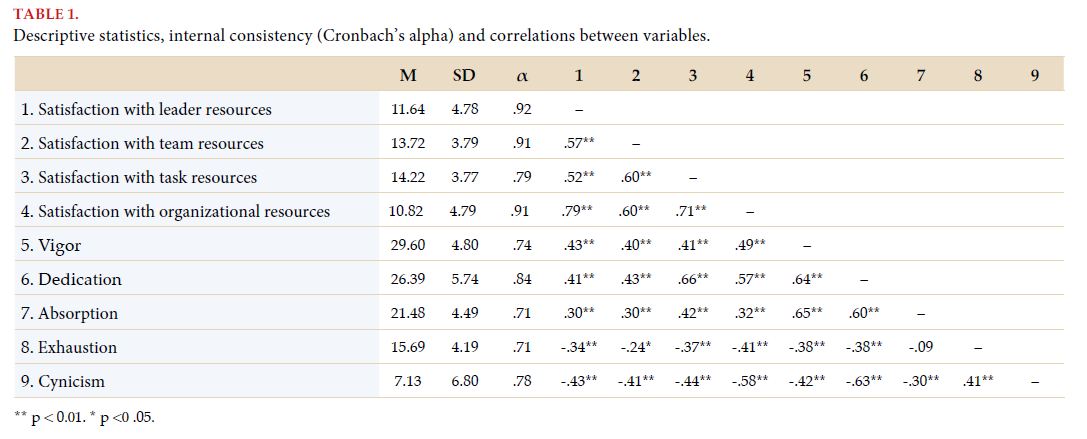

Mean, standard deviation, reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for each variable and their correlations to each other are presented in Table 1. Positive relationships and of moderate and strong magnitude (r values between 0.30 and 0.66, M=0.43) between the satisfaction of work resources (leader, team, task and organizational) and the work engagement dimensions were observed. Likewise, satisfaction with work resources presented negative relationships with burnout dimensions, with relationships also being moderate and strong (r between -0.25 and -0.58, M=-0.40).

DISCUSSION

According to Babaian, the COVID-19 pandemic presented four waves. The fourth wave is the most important and refers to the mental disorders derived from the financial and social events related to the pandemic[34]. In this fourth wave, one of the most vulnerable groups are health care workers, due to the highly stressful conditions to which they are exposed. Consequently, the development of interventions with a preventive approach oriented to averting the appearance of unwanted psychological consequences, such as burnout, becomes more important than

At international level, scientific investigation about burnout in sanitary professionals appears to be very active, with the influence of demographic factors (e.g., gender, age, educational level, marital status) and occupational factors (e.g., role or function, area, type of specialty) standing out[26,27,35]. Although these studies allowed us to advance in the knowledge of background factors of burnout and the identification of subgroups that present a greater risk, they are often personal characteristics or intrinsic to the job, difficult or impossible to modify by intervention. Therefore, it is necessary to continue developing studies that may analyze psychosocial factors and their potential impact on the mental health of health care workers, within the specific scenario of the pandemic. This study set out to analyze the influence of satisfaction with work resources on burnout and on work engagement.

The results show that satisfaction with the different work resources (leader, task, team and organizational) are significantly associated with the burnout and work engagement levels of health care workers. Particularly, satisfaction with resources is associated to lower levels of burnout and greater levels of work engagement. Globally, these results coincide with those reported in pre-pandemic studies, although the relationships observed are consistently stronger in this investigation, which manifests the relevance of satisfaction with work resources in the psychological wellbeing of sanitary professionals in a scenario of pandemic[18]. On the other hand, regression analysis showed that satisfaction with work resources explained, jointly, between 14% and 36% of variance in the burnout and work engagement dimensions, above and independently from the socio-demographic and occupational characteristics of workers. Specifically, from satisfaction with the four resources studied, the main predictor was satisfaction with organizational resources, contributing positively to predicting vigor and dedication, and negatively to predicting exhaustion and cynicism. Satisfaction with task resources also showed a significant predictive contribution, being the factor with highest predictive power for dedication and absorption, while it also contributed negatively in the prediction of exhaustion. Finally, satisfaction with social resources showed a lower contribution than organizational and task resources, but significant. Specifically, satisfaction with team resources contributed negatively to prediction of cynicism; while satisfaction with leader resources positively predicted vigor and absorption. In summary, satisfaction with organizational resources, task resources and with leader resources positively contributed to predicting work engagement; while satisfaction with organizational resources, and to a lesser extent, team resources, negatively contributed to prediction of burnout.

The results obtained allow us to make some practical recommendations in order to protect mental health and the wellbeing of health care workers. About this, numerous tools and interventions have been proposed, oriented at maintaining the psychological wellbeing of health care professionals and at helping to cope with difficult situations, including mindfulness sessions, educational videos about healthy feeding, guidelines for health care and physical and psychic wellbeing, sleep hygiene, prevention of anxiety and stress, among others[36]. To a large extent, they are interventions at individual level, addressed either to controlling stressors or developing coping resources to soften their impact. Faced with overemphasis on interventions based on individual effort, from the HERO model the proactive role of organizations on caring for employees is emphasized, through the development of healthy organizational practices[19]. The results of this investigation suggest that organizations dedicated to health care may contribute to the wellbeing and the health of their employees, by four foci of intervention: (1) by increasing satisfaction with organizational resources; for instance, by a program of actions that may include an updated system of non-financial benefits and compensations according to the requirements of workers (management of schedules and shifts, special permits, programs for specific training to deal with COVID-19, facilitation and development of professional career plans), as well as equitable and fair financial compensations; (2) by enhancing satisfaction with task resources, by a balance between challenges and skills at work position level, promoting autonomy, facilitating tools for control and time managements, and ensuring availability and a proper operation of necessary teams, materials and supplies to develop tasks safely; (3) by improving satisfaction with leader resources, by developing transformational leading skills in chiefs and supervisors, generating admiration, inspiring collaborators, instilling confidence and courage to deal with crises, and being receptive and empathetic to their needs, with special attention to emotional needs and care of work teams; and (4) by increasing satisfaction with team resources, through the acknowledgement of group achievements, attention to fair criteria in the distribution of tasks, the development group skills of management and problem-solving, and the generation of spaces addressed to sharing learning, emotions, experiences and methodologies, which enable generating and strengthening team resources, as well as a shared feeling of support, pride and collective self-efficacy. Given that burnout and work engagement are “contagious” between workers, this type of interventions could not just help to mitigate burnout and enhance work engagement at individual level; but also, at organizational-collective level, contributing to the development of healthy and resilient sanitary organizations[37,38,39].

Beyond the implications pointed out, it is necessary to take into account that results are based on a small sample of sanitary professionals from a private health care institution. Therefore, it would be worthy to replicate the research with wider and representative samples of health care workers, including sanitary staff both from the public and the private sectors. Likewise, the results of this study are based on the analysis of the general sample of health care workers, independently from particular demographic (e.g., gender, age) and occupational (e.g., specialty, work area, career) characteristics. Given evidence indicating that these variables moderate the psychological impact of the pandemic on health care professionals[26,27,35], it is necessary to continue doing investigations that will allow a more refined understanding of the results of this study. Also, it would be interesting to analyze the influence on the studied variables, particularly burnout, associated to the experience of having been infected with COVID-19, or not. On the other hand, investigations in different parts of the world within the framework of the pandemic indicate a high prevalence of different emotional disorders, besides burnout, like anxiety and depression in the medical staff[7,40,41]. Considering this, in the future it would be useful to extend this investigation by analyzing the impact of satisfaction with work resources on anxiety and depression. Likewise, although in this study the influence of satisfaction with work resources on burnout and work engagement was verified, the design was cross-sectional, so it is not possible to assume a causal influence. In this regard, although the investigation indicates that resources constitute a background for work engagement and burnout, there is also evidence that work engagement and burnout may influence on the perception of work resources, so it would be feasible to assume they also influence on judgements on satisfaction with resources[42,43,44]. The development of cross-sectional studies that would study the relationships between the study variables under different models (direct, inverse and reciprocal causality) could be very useful to clarify the nature of the relationship between satisfaction with work resources, on the one hand, and work engagement and burnout on the other. Finally, in this study satisfaction with work resources was the focus. It would be convenient in the future to analyze the impact of personal resources, such as optimism, hope and self-efficacy. These resources not only promote work engagement, but also allow actively facing crises scenarios in a healthy manner, learning and strengthening from them (resilience resources)[45]. Particularly, it would be interesting to analyze the possible mediating effect of personal resources between satisfaction with work resources and work engagement and burnout, to better understand the mechanisms through which satisfaction with resources influences on the wellbeing of health care workers in times of crisis.

CONCLUSIONS

The COVID-19 pandemic represented a novel situation for the world, generating a health care overload and health care systems saturation. In such scenario, several investigations have shown the negative emotional impact of the pandemic on health care professionals, with psychological consequences that extend over time[8]. For this reason, the study of the factors that underlie psychological discomfort (e.g., burnout) and of those that help to preserve mental health and wellbeing (e.g., work engagement), in scenarios of crisis becomes vital for the design of measures that would allow taking care of the health of workers and being better prepared for the future, when faced with possible sanitary crises. The results of this work show the importance of satisfaction with work resources, particularly with organizational and task resources, and suggest a series of measures or recommendations that could be useful for, in the future, protecting health care workers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Director Gisela Veritier, M.Sc. Luis Maffei and M.D. Eddie Moreyra due to their commentaries on this paper and their collaboration given in data collection. This study has been made with the financial support of the Instituto de Ciencias de la Administración -ICDA (Institute of Administration Sciences) of the Universidad Católica de Córdoba – UCC, Argentina, and the Sanatorio Allende.

BIBLIOGRAPHY