Original Article

Clinical characteristics, treatment and complications of patients with acute myocardial

infarction and atrial fibrillation. Analysis of 5,708 cases from the National Registry

ARGEN-IAM-ST

Gerardo Zapata MTFAC 1, Fernando Bagnera MTFAC 1,

Rodrigo Zoni MTFAC 1,

Camila Antonietta MTFAC 1, Heraldo D´ imperio2, Yanina Castillo Costa2, Adrián Charask2,

Juan Gagliardi2,

Eduardo Perna MTFAC 1.

1 Federación Argentina de Cardiología. 2 Sociedad Argentina de Cardiología

Corresponding author’s address

Dr. Gerardo Zapata

Postal address: Riobamba 2862 (2000) Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina.

E-mail

INFORMATION

Received on May 15, 2022

Accepted after review

June 18, 2022 www.revistafac.org.ar

There are no conflicts of interest to

disclose.

Keywords:

Myocardial infarction .

Atrial fibrillation .

National Registry ARGEN-IAM-ST.

ABSTRACT

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common type of sustained arrhythmia observed

in acute myocardial infarction with persistent ST-segment elevation (STEMI). It can be

preexistent or part of a complication, which often allows the identification of groups in higher

risk. This study was designed to evaluate the clinical characteristics, therapeutic management

and in-hospital prognosis in the aforementioned population of patients.

Methods: Patients included in the national registry ARGEN-IAM-ST were studied, identifying

those with AF. The treatments provided and in-hospital prognosis were assessed.

Results: A total of 5,708 patients participated, of whom 5.7% (n=323) constituted the “AF

group”. Of these, 44% presented with AF from the start and the remaining 56% developed some

event during hospitalization. The patients in the AF group were older (68.7 years [60-76.5] vs. 60

years [53-68]; p<0.001), and had a higher prevalence of hypertension (73.4% vs. 58%; p<0.001) and

coronary revascularization or infarction (18% vs. 13%; p: 0.008). They also received less treatment

with aspirin (88.4% vs. 96.5%; p<0.001) and strong antiplatelet agents (12.7% vs. 25.5%; p<0.001).

In these patients, higher rates of stroke (3.1% vs. 0.8%; p<0.001), bleeding (8.7% vs. 2.4%; p<0.001) and inhospital

mortality (22.9% vs. 7.8%; p<0,001) were observed.

Conclusions: In this population of patients with STEMI, the subjects of the AF subgroup were older, had

more comorbidities, and were associated with higher rates of in-hospital events.

ABBREVIATIONS

Registro nacional de infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (National Registry of ST-elevation myocardial infarction): ARGEN-IAM-ST

ST-elevation myocardial infarction: STEMI

Atrial fibrillation: AF

Sociedad Argentina de Cardiología (Argentine Society of Cardiology): SAC

Federación Argentina de Cardiología (Argentine Federation of Cardiology): FAC

Primary angioplasty: PTCA

INTRODUCTION

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a disease with high incidence and mortality. In its acute phase, the appearance of supraventricular arrhythmias may constitute a very frequent scenario, and occasionally, it may make management complex[1].

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the type of sustained arrhythmia most widely observed, the incidence of which ranges from 6 to 21% of cases, with a clear predominance in the elder population[2].

AF may preexist or could be part of a complication of STEMI, often identifying groups in greater risk. Significant studies reported the appearance of AF over the course of STEMI was associated to a marked increase in mortality and stroke[3,4,5,6,7].

There are few data in Latin America and particularly in Argentina, which describe AF behavior in this scenario. The Registro nacional de infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (National Registry of ST-elevation myocardial infarction - ARGEN-IAM-ST) is conducted by the Sociedad Argentina de Cardiología (SAC) and the Federación Argentina de Cardiología (FAC)[8,9].

The aims of this study were to evaluate the clinical characteristics, therapeutic management and in-hospital prognosis of AF appearance in a population of patients included in the ARGEN-IAM-ST registry.

METHODS

The characteristics of the ARGEN-IAM-ST registry have been previously described[8,9]. In brief, this is a prospective, multicenter, national and observational registry, coordinated by SAC and FAC. A first stage included a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of STEMI patients within the first 36 hours of evolution, from November 2014 to December 2015. Since 2015 to this date, the ongoing registry continues.

The inclusion criteria to the registry were a strong suspicion of infarction, with some of the following: 1) ST-segment elevation ≥1 mV in at least two limb leads or ≥2 mV in at least two contiguous precordial leads; 2) infarction coursing with new Q waves of at least 36 h since the onset of symptoms; 3) suspicion of inferior-posterior infarction (ST-segment horizontal depression from V1 through V3, suggesting acute occlusion of circumflex artery); or 4) new or presumably new complete left bundle branch block.

The exclusion criteria were diagnosis of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome and infarctions having coursed for more than 36 hours.

For this study, patients with electrocardiogram available (ECG on inclusion to the registry) were included.

This analysis incorporated the data included until July 2021. A description was made on the characteristics of the population, identifying the patients that were admitted with AF or developed episodes during hospital stay. The treatments applied and in-hospital outcome were evaluated in the different groups.

Data collection:

Data collection was made through the web, in an electronic file, especially designed by the Centro de Teleinformática Médica (Medical Teleinformatics Center) of FAC (CETIFAC), which enabled on line monitoring for the uploaded variables. The patients’ privacy in the registry was guaranteed as the names or initials of patients were not saved in the database, and they were identified by a correlative number by center.

Statistical analysis:

The qualitative variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and the quantitative ones as mean±standard deviation (SD) or mean and interquartile range 25-75% (IQR) according to distribution. The analysis of discrete variables was made through the chi square or Fisher’s exact test and that of continuous variables with Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as it corresponded. All statistical comparisons were two-tailed and p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. With the variables significantly associated with mortality in univariate analysis, a multiple logistic regression model was built to identify independent predictors of the endpoint of mortality. Data analysis was made with the Rstudio 2021.09.0 software.

Ethical considerations:

The protocol was evaluated and approved by the Committee on Bioethics of SAC and the Department of Education of FAC. Depending on local regulations and institutional policies, the protocol was subjected to evaluations by local committees.

RESULTS

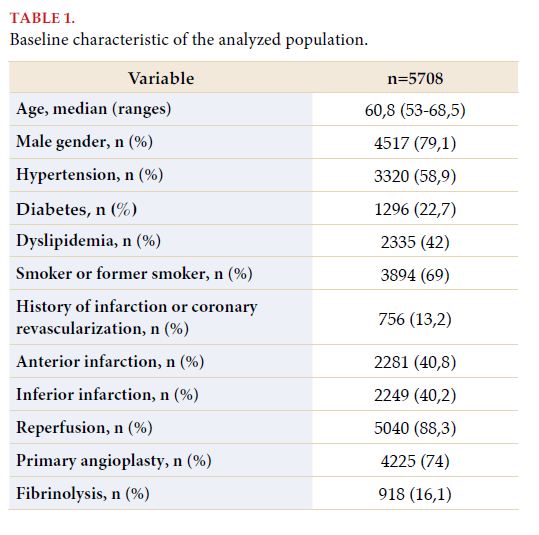

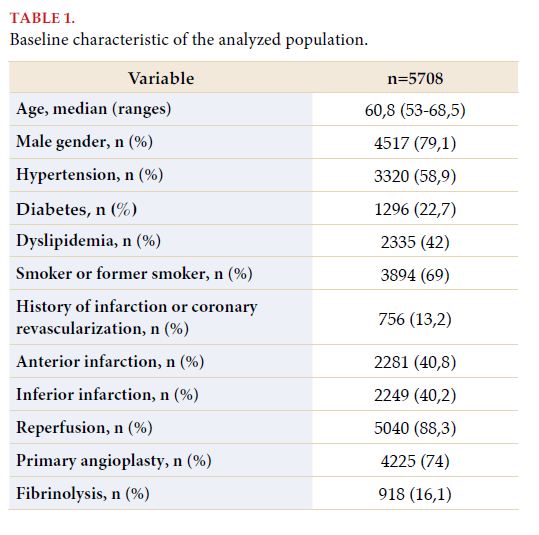

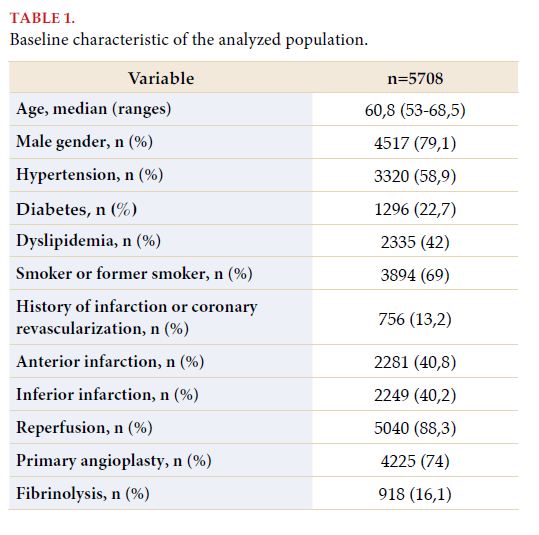

The sample was constituted by 5,708 individuals, whose characteristics are provided in Table 1. From them, 79.1% (n=4517) were males, and the mean age was 60.8 years (53-68.5). The infarctions were located in the anterior (n=2281) and inferior walls (n=2249) in identical percentages (40%), with 91.4% being categorized in Killip-Kimball (KK) classes 1 or 2; and 88.3% (5040) received some reperfusion strategy, from whom 16.1% was thrombolysis and the rest primary angioplasty (PTCA) of the culprit vessel.

The “AF group” represented 5.7% (n=323) of the total. From these, 44% presented with AF since the beginning and the remaining 56% presented some episode during admission.

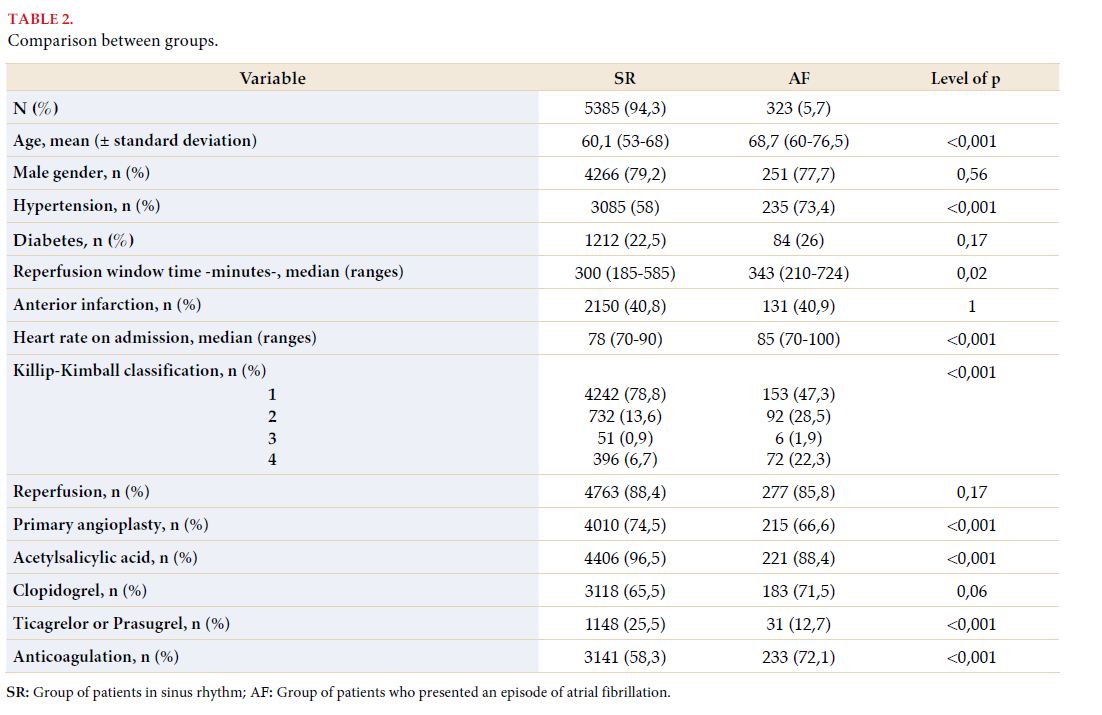

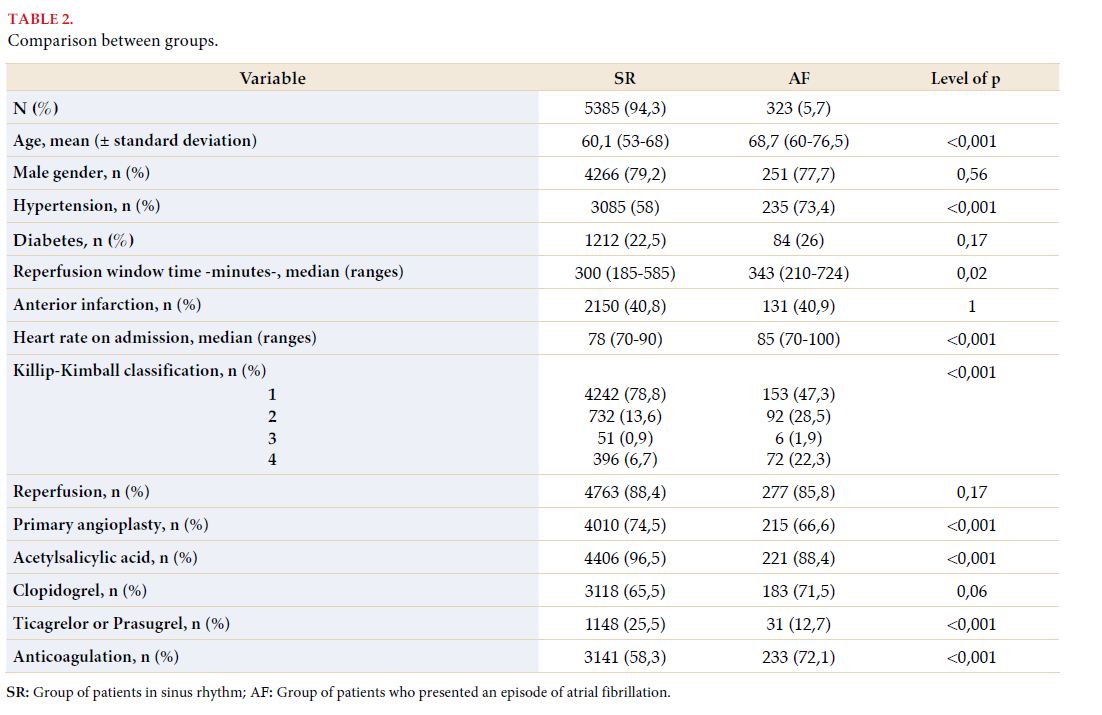

The AF group patients were older (68.7 years [60-76.5] vs 60.1 years [53-68]; p<0.001) and displayed more prevalence of hypertension (73.4% vs 58%; p<0.001) and history of infarction or coronary revascularization (18% vs 13%; p=0.008). No significant differences were found in terms of type of infarction and reperfusion rates; although patients with AF underwent less PTCA (66.6% vs 74.5%; p=0.002). Moreover, window times were higher in this group (343 minutes [210-724] vs 300 minutes [185-585]; p=0.02); as well as the percentage of patients who presented with KK scores equal or greater than 2 (52.7% vs 21.2%; p<0.001).

About the adjuvant treatment established, it is observed that patients with AF received acetylsalicylic acid (88.4% vs 96.5%; p<0.001) and strong antiplatelet drugs (ticagrelor and prasugrel) (12.7% vs 25.5%; p<0.001), with greater percentages of anticoagulated individuals (72.1% vs 58.3%; p<0.001) (Table 2).

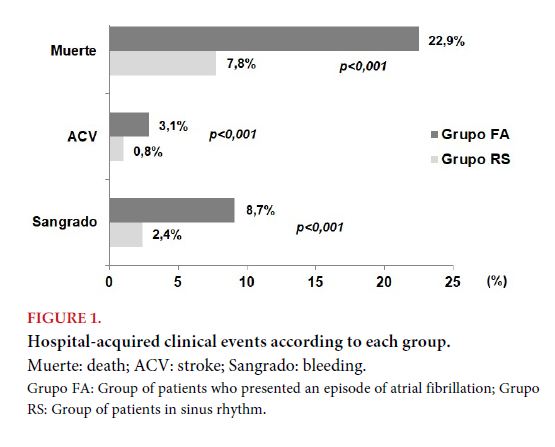

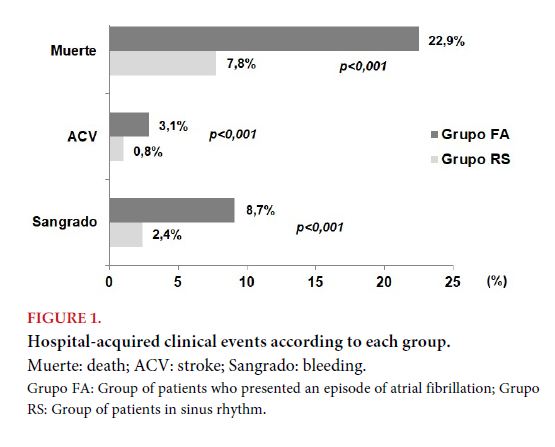

In the “AF group”, greater rates of strokes were observed, not discriminated by being ischemic or hemorrhagic (3.1% vs 0.8%; p<0.001), bleeding (8.7% vs 2.4%; p<0.001) and in-hospital mortality (2.9% vs 7.8%; p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Multivariate analysis identified diabetes and KK score as independent predictor variables of death, with a non-significant trend being observed in the “AF group” (OR: 1.52; 95% CI: 0.98-2.32; p: 0.06) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were learning about local data related to the appearance of AF in patients coursing STEMI and its association with rate of in-hospital adverse events. These results are in coincidence with the international bibliography, where an important meta-analysis confirmed the appearance of such arrhythmia as a powerful predictor of adverse outcome[2].

Incidence of AF in STEMI

In this local registry, it was observed that the percentage of patients presenting AF represented 5.7% of the whole sample. In the last three decades, we witnessed a revolution in the management of STEMI, with different reperfusion therapies extending massively, initially with thrombolysis, and currently, (as present data show) with PTCA. Thus, we have seen that the incidence of AF as a complication of STEMI decreased from 18% in 1990 to 11% in 1997[10]. Besides, the adjuvant treatment of the acute phase of infarction has changed, where great benefits had been proven when using beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or aldosterone receptor antagonists, in selected groups of patients. For instance, in the TRACE study, a reduction of 5.3% was shown in the incidence of AF during hospitalization in patients treated with trandolapril in comparison to those randomized to placebo[11]. Even lower incidences were observed in the OPTIMAAL trial, which evaluated captopril[12]. In the CAPRICORN, the percentage of AF as a complication of infarction reduced from 5.4 to 2.3% when administering carvedilol (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.25-0.68; p=0.0003). It is thus observed that different therapies had an influence on the reduction of these figures, which are close to the figures presented in this study[13].

Subtypes of AF

From the total of patients included in this study, 2.5% presented with AF since the beginning and the remaining 3.2% presented some episode during admission. An important Sweden study that included 155,071 individuals that had coursed an acute coronary syndrome studied this issue, documenting AF in 15.5% of the total. In turn, this was classified into subtypes, which were: new onset AF with sinus rhythm on discharge (3.7%), new onset AF with AF on discharge (3.9%), paroxysmal AF (4.9%) and chronic AF (3.0%)[14]. We should highlight that in this study, AF was more frequent in patients that presented with no ST-segment elevation, much older individuals, and those with more comorbidities than those with STEMI. New onset AF seems to be the most frequent subtype in this and other studies with less sample size[6,15].

Clinical characteristics associated to AF development

In this cohort, we observed that patients presenting AF were older and showed more prevalence of hypertension and history of infarction or coronary revascularization. In spite of what was commented above, a decrease was observed in AF figures in this scenario, due to the increase in life expectancy in the population, so it is expected for AF to remain a problem observed with relative frequency. Furthermore, the percentage of patients who were admitted with KK scores equal or higher than 2 doubled those that remained in sinus rhythm. A multivariate model formulated from a significant international database identified advanced heart failure as the strongest predictor of AF development in this scenario[16]. Others were a high heart rate, probably due to pump failure, and older age. These variables were also described in other series of patients regardless of the type of reperfusion strategy, categorizing this population as a subgroup in high clinical risk.

Antithrombotic treatment

The ARGEN-IAM-ST registry is a representation of treatment strategies in real life in our country. In a recent study published by Muntaner et al, 24% of patients were treated with “new or strong antiplatelet drugs” (prasugrel or ticagrelor)[17]. These figures reduce to a half in patients with AF, a logical scenario when taking into account the need to associate an anticoagulant in his group, with the entailed increased risk of bleeding. It was also observed that individuals with AF received acetylsalicylic acid to a lesser extent.

In-hospital events

It has been proven that in the general population, AF is associated to more morbimortality, being mainly related to the comorbidities carried by the group where it is usually diagnosed[18]. It is also known that lone atrial fibrillation in younger individuals with no heart disease does not have a clear association with adverse outcome[19]. In the context of STEMI, just as previously commented, its presence is very well documented as a strong predictor of poor evolution. In the GUSTO I study, a clinical trial that randomized 40,891 patients with infarction, where two thrombolysis strategies were compared, those developing this arrhythmia presented a significantly greater in-hospital mortality, besides observing greater figures of other events such as re-infarction, cardiogenic shock, heart failure and asystole (p=0.001). Mortality rates at 30 days showed OR of 1.3 (CI 95% 1.2-1.4)[5]. Similarly, in a large database of patients in an advanced age, the development of AF during hospitalization was associated to an increase in mortality during the hospital stay (OR 1.39; 95% CI 1.28-1.42) and within the first 30 days (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.25-1-37)[16]. On the contrary, in those that presented AF at the time of admission, similar results were observed to those in sinus rhythm, marking new onset AF as a manifestation of acute hemodynamic compromise. In consonance with bibliography, the data from this study show similar results. In-hospital mortality was greater in the AF group (22.9% vs 7.8%; p<0.001), also being associated to stroke rates higher than those recorded in the control group (3.1% vs 0.8%; p<0.001). In GUSTO I, the same percentage of patients with AF suffered stroke (mainly ischemic), compared to only 1.3% in those in sinus rhythm (p<0.001), although more complete information in relation to this topic could be provided by the OPTIMAAL trial, where new onset AF was associated to a greater than tenfold increase in the risk of stroke in follow-up (30 days)[5,12]. Therefore, there is evidence indicating AF would increase the risk of stroke both on admission and in follow-up, not just in individuals discharged in this rhythm, but also in those presenting paroxysms and discharged in sinus rhythm.

LIMITATIONS

In spite of the number of patients enrolled being the largest recorded to this date, the study constitutes a subanalysis of the main registry, with the implications entailed by this.

CONCLUSIONS

In this population of patients with STEMI from the ARGEN-IAM-ST registry, the rate of AF was 5.7%. This subgroup included older individuals, with more comorbidities, receiving less antiplatelet management and presenting more in-hospital complications. .

KEY POINTS

There are no data in Argentina, and very few in Latin America, about the behavior of atrial fibrillation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. This study provides data on the frequency of association of these pathologies, characteristics of the population, treatment and outcome in a large series of cases in Argentina.

Acknowledgements

To the investigators of each participating center.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- James TN. Myocardial infarction and atrial arrhythmias. Circulation

1961; 24: 761–776..

- Schmitt J, Duray G, Gersh BJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial

infarction: a systematic review of the incidence, clinical features and

prognostic implications. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1038 - 1045

- Pizzetti F, Turazza FM, Franzosi MG, et al; GISSI-3 Investigators. Incidence

and prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial

infarction: the GISSI-3 data. Heart 2001; 86: 527 - 532.

- Wong CK, White HD, Wilcox RG, New atrial fibrillation after acute myocardial

infarction independently predicts death: the GUSTO-III experience.

Am Heart J 2000; 140: 878 - 885.

- Crenshaw BS, Ward SR, Granger CB, et al. Atrial fibrillation in the setting

of acute myocardial infarction: the GUSTO-I experience. Global Utilization

of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll

Cardiol 1997; 30: 406 - 413.

- Mehta RH, Dabbous OH, Granger CB, et al; GRACE Investigators. Comparison

of outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes with and

without atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92: 1031 - 1036.

- Lopes RD, Pieper KS, Horton JR, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes following

atrial fibrillation in patients with acute coronary syndromes with

or without ST-segment elevation. Heart 2008; 94: 867 -873.

- Gagliardi JA, Charask A, Perna E, et al. Encuesta nacional de infarto agudo

de miocardio con elevación del ST en la República Argentina (ARGENIAM-

ST). Rev Argent Cardiol 2016; 84: 548 - 557.

- Gagliardi JA, Charask A, Perna E, et al. Encuesta nacional de infarto agudo

de miocardio con elevación del ST en la República Argentina (ARGENIAM-

ST). Rev Fed Arg Cardiol 2017; 46: 15 - 21.

- Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, et al. Recent trends in the incidence

rates of and death rates from atrial fibrillation complicating initial acute

myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Am Heart J 2002;

143: 519 - 5127.

- Pedersen OD, Bagger H, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C. The occurrence and

prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation/-flutter following acute myocardial

infarction. TRACE Study group. TRAndolapril Cardiac Evalution.

Eur Heart J 1999; 20: 748 - 754.

- Lehto M, Snapinn S, Dickstein K, et al; OPTIMAAL investigators. Prognostic

risk of atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction complicated

by left ventricular dysfunction: the OPTIMAAL experience. Eur Heart J

2005; 26: 350 - 356.

- McMurray J, Køber L, Robertson M, et al. Antiarrhythmic effect of carvedilol

after acute myocardial infarction: results of the Carvedilol Post-

Infarct Survival Control in Left Ventricular Dysfunction (CAPRICORN)

trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45: 525 - 530.

- Batra G, Svennblad B, Held C, et al. All types of atrial fibrillation in the

setting of myocardial infarction are associated with impaired outcome.

Heart. 2016; 102: 926 - 933.

- Maagh P, Butz T, Wickenbrock I, et al. New-onset versus chronic atrial

fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: differences in short- and longterm

follow-up. Clin Res Cardiol 2011; 100: 167 - 175.

- Rathore SS, Berger AK, Weinfurt KP, et al. Acute myocardial infarction

complicated by atrial fibrillation in the elderly: prevalence and outcomes.

Circulation 2000; 101: 969 - 974.

- Muntaner J, Cohen Arazi H, Mrad S, et al. Estrategia antiplaquetaria en el

Registro ARGEN-IAM. Rev Fed Arg Cardiol 2021; 50: 65 - 69.

- Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation

on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998; 98:

946 - 952.

- Kopecky SL. Idiopathic atrial fibrillation: prevalence, course, treatment,

and prognosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 1999; 7: 27 - 231